Concussion Litigation in Rugby – Part I: Duty of Care

1. Introduction

In December 2020, legal action was instigated by a group of former professional rugby players against the Rugby Football Union (“RFU”), the Welsh Rugby Union (“WRU”) and World Rugby, the sport’s International Federation.

A pre-action letter of claim was reportedly sent on behalf of nine players, including former England internationals Steve Thompson and Michael Lipman, and former Wales flanker, Alix Popham. The players are arguing that the governing bodies failed to adequately protect them from the risks associated with concussion, which has resulted in eight of the nine players being diagnosed with early-onset dementia and probable chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE).

This series of articles will analyse the litigation in detail, considering each of the key legal issues that are likely to arise. For the avoidance of doubt, this author has no direct knowledge of the proceedings and, as such, will avoid speculating as to the precise facts.

Given that the players so far involved in the litigation played the majority of their rugby in England or Wales, it shall be assumed the law of England and Wales shall be applicable to the dispute, and that the English courts will have jurisdiction.

The players’ claims will be brought in the tort of negligence. For any negligence claim, a claimant much show that the defendant (i) owed them a duty of care; (ii) breached that duty of care; and (iii) that this breach of duty caused the claimant to suffer loss. If successful, the claimant will recover damages for their losses, though there are various defences which may be available to a defendant.

This series will broadly follow that structure. Part I will consider whether rugby’s governing bodies owed the players a duty of care, Part II will ask whether they may have breached that duty, while Part III will analyse the issues of causation. Part IV will then consider the possible defences the governing bodies might have, Part V will explain how damages would be determined, and Part VI will discuss the group litigation element, possible jurisdictional difficulties, and the possibilities of settlement.

A final introductory point worth making is that this legal action will not necessarily be the same as the NFL concussion litigation. Though there will inevitably be similarities, several issues are likely to be distinct, which will be highlighted throughout this series. Notably, the NFL never formally admitted liability, and the case settled without a trial.

2. The duty of care in English law

In English law, determining when a duty of care will arise is not always straightforward. Various legal tests have developed over the years, identifying a number of relevant factors but there is no “general principle capable of providing a practical test applicable in every situation”.[1]

Following the recent decision of the UK Supreme Court in Darnley v Croydon NHS Trust,[2] a duty of care will exist in two scenarios. First, and un-controversially, there will be a duty of care where one has already been recognised in that particular context (in other words, where there is an existing precedent).[3]

Second, in “novel situations”,[4] there will be a duty of care where it would be fair, just, and reasonable to impose such a duty; damage is reasonably foreseeable; and there is a sufficiently proximate relationship between the parties – in other words, on application of the Caparo factors.[5] In this second category, the courts will consider whether a duty of care should be extended to such a situation “on an incremental basis, accepting or rejecting a duty of care in novel situations by analogy with established categories”.[6] This test will also be used to determine the scope of the duty of care.

If such a duty exists, the party who owes the duty will be under an obligation to take reasonable care in respect of those to whom it is owed. As regards what is “reasonable”, see Part II.

3. Duties of care in sport

The existence of a duty of care, or perhaps more importantly its scope, is a crucial element of the rugby concussion litigation. Without a duty of care, there can be no claim.

At present, it seems that the claims will be brought against the RFU and the WRU (the “Unions”), and World Rugby – all governing bodies. It is foreseeable, too, that clubs (and perhaps leagues) may yet become involved. What, then, is the legal position in respect of these entities?

3.1 The Governing Bodies

The leading English case as regards the duty owed by sports governing bodies is Watson v British Board of Boxing Control.[7] In that case, Michael Watson brought a claim in negligence after being severely injured in a fight against Chris Eubank. He argued (successfully) that there was a lack of adequate ringside medical facilities and that this caused his serious brain damage, which had been avoidable.

Crucially, for present purposes, the Court of Appeal held that the BBBoC owed Watson a duty of care – despite the fact that it was not the organiser of the fight. The court found that because the BBBoC set down minimum mandatory requirements (which had been followed by the promoters), there was a sufficiently proximate relationship[8] and thus a duty to take reasonable care to ensure that personal injuries are properly treated. The mandatory requirements themselves were inadequate.

Lord Phillips MR drew a distinction between “making Rules and giving advice”,[9] emphasising that by creating mandatory rules in relation to the provision of ringside medical treatment, there was proximity between the parties. He further noted that this was so because the BBBoC had medical expertise available to it, and “held itself out as treating the safety of boxers as of paramount importance”.[10] Further, boxers could not themselves be expected to know what were reasonable measures to take, such that Mr Watson was reasonably entitled to rely upon the expertise of the BBBoC for his proper medical treatment – a further indicator of proximity.[11]

Many of these factors were also relevant to the wider question of whether it was fair, just and reasonable for a duty of care to be imposed. The BBBoC controlled every aspect of the sport (including medical facilities), it assumed responsibility for the standards of medical care, and it was a stated object of the BBBoC to look after its members’ physical safety.[12] With damage being quite obviously reasonably foreseeable, the BBBoC was found to owe a duty of care.

So, does this decision mean that a duty of care is already established for rugby’s governing bodies, or are we in a “novel” situation? In his judgment, Lord Phillips MR made clear that he was not “formulating a principle of general policy”,[13] but the case is certainly somewhat analogous. It seems to this author that the rugby litigation will require a small “incremental” extension of the duty of care to rugby’s governing bodies.

3.1.1 World Rugby

As the international governing body for rugby union, World Rugby is the ultimate controller of the sport worldwide. It determines the Laws of the Game and sets out regulations with which participants and Unions must comply,[14] including on concussion-related matters.[15] It thus assumes a position similar to that of the BBBoC in Watson, as a rule-maker (not merely an advisor) albeit on a global level.

Notably, this is not the first time that World Rugby’s duty of care owed has been considered. In 2000, the High Court of Australia held in Agar v Hyde[16]that the International Rugby Football Board (now World Rugby) owed no duty of care to amateur players who had suffered severe spinal injuries in the scrum.

However, this author is of the view that the court’s reasoning in Agar was erroneous. In its judgment, the court referred to the “obvious risk of injury” and voluntary participation as reasons to deny the existence of a duty of care. [17] Yet, while these factors might be relevant to the question of breach (i.e. what was reasonable) or the defence of volenti non fit injuria, they have no place in assessing whether a duty of care should be imposed. It also held that liability would be “indeterminate”[18] and that the “content of the suggested duty is elusive”.[19] Concerns about indeterminate liability are misplaced, as only those who play the sport under the Laws of the Game would be owed a duty – a determinable class of people.

Nor is the content of such a duty elusive. Here we are not concerned with the duty to provide adequate medical facilities, as in Watson, but with a duty to take reasonable care to protect the health and safety of rugby players. Specifically, this would include reasonably protecting rugby players against brain injuries, including the long-term effects of repetitive head trauma. Such a duty might incorporate a duty to inform players of the risks to their health, a duty to carry out research in relation to the risks associated with repeated head trauma, and a duty to (reasonably) minimise these risks, including by adjusting the way that the game is played and/or refereed, and a duty to enforce existing regulations. There would be no duty to eliminate brain injuries, merely to act reasonably to mitigate the risks.

The very fact that World Rugby has, in the past decade, amended its rules and regulations to reduce the risks of players suffering concussions on the rugby pitch,[20] and to better protect those who do,[21] suggests that it has assumed responsibility for the well-being of players. Indeed, one of World Rugby’s slogans is “Putting players first”. These factors point towards there being a proximate relationship between players and World Rugby, and it being fair, just and reasonable to impose a duty of care.

Of course, the conduct at the heart of the reported claims pre-dates the past decade. As such, these factors may be of limited relevance. Nonetheless, World Rugby (or the International Rugby Board as it then was) has long since had mandatory regulations on the treatment of concussion and in Agar, the court noted that it was “common ground that, from time to time, rules are changed with considerations of safety in mind”.[22] As in Watson, players are quite clearly entitled to rely on the measures laid down by World Rugby – in reality they have no choice but to do so.

In the case of Wattleworth v Goodwood,[23] the International Federation for motorsport, the FIA, was found not to owe a duty of care to a driver in respect of the layout of the circuit and the safety barriers in place while the national governing body, the Motor Sports Association, did. Crucial to this decision was the fact that the FIA took merely an advisory role rather than a rule-making role, and there was thus no proximity.[24] The court also held that, as between the MSA and the FIA:

“a line should be drawn somewhere…the more so when, by reason of its involvement in international events, the FIA has to concern itself with many scores of countries other than the United Kingdom and essentially primarily entrusts circuit safety matters to national sporting authorities.”[25]

World Rugby’s role is distinct. While the FIA had guidelines on safe circuit design, these were not binding on Goodwood, and the FIA had no responsibility for the non-international event at which Mr Wattleworth was injured. Though the implementation of its regulations is primarily entrusted to the Unions, World Rugby imposes minimum requirements in the context of brain injuries. There are also certain fundamental matters relating to the game, which the Unions are unable to affect.[26]

World Rugby has procedures in place to enforce compliance with its regulations (including its medical and concussion-related regulations)[27] and controls most safety aspects of the sport, albeit indirectly, via the Unions. Its role, at least in the present context, is far more akin to the BBBoC’s role in Watson than to the FIA’s role in Wattleworth. There is thus greater proximity.

World Rugby is far better placed than players to determine the appropriate measures that ought to be taken to ensure the reasonable safety of participants. It is also likely to be insured against the risks of breaching such a duty of care. It is fair, just, and reasonable to impose a duty of care.

3.1.2 The Unions

The picture is largely the same for the Unions. They are the primary regulators of rugby union in their respective jurisdictions and, though they are bound by World Rugby’s regulations, are able to go beyond such minimum standards.

Matches in England must be held under the authority of the RFU and its own mandatory regulations and players must be registered with the RFU. The RFU produces its own minimum standards on brain injuries and medical treatment[28] and conducts a thorough injury surveillance project of the professional game. Though the RFU is led by World Rugby on major regulatory changes, it is clear that the RFU has assumed responsibility for the health and safety of players in England – and the same can likely be said of the WRU in Wales.

Players must reasonably be entitled to rely on the measures put in place by their Union, and the proximity between players and their Unions is arguably greater than with World Rugby, as the relevant regulations are enforced directly by the Unions.

Given the position of and responsibilities assumed by the Unions, it is fair, just, and reasonable to impose a duty of care in respect of the players within their jurisdictions. RFU CEO Billy Sweeney has also admitted that the RFU has insurance cover for such claims.

Nonetheless, the scope of the duty may well be different to that owed by World Rugby. In this context, the duty of care of the Unions might include a duty to ensure that World Rugby’s concussion-related regulations are reasonably complied with, a duty to inform players of the risks to their health, a duty to carry out research in relation to the risks associated with repeated head trauma, and a limited duty to (reasonably) minimise these risks. However, such a duty could not extend to amending the Laws of the Game or changing the way that the game is played – at least at elite level. Such responsibility lies exclusively with World Rugby.

It is clear that their respective duties will overlap to a degree – though what is expected of World Rugby may well exceed that which is expected of the Unions. The degree to which these overlapping duties can be reconciled will largely be dealt with at the ‘breach’ stage, when considering what it is reasonable for each party to do. It should not, in this author’s view, deny the existence of a duty of care.

3.2 Employers

Aside from the likely regulatory duties of care owed to players, their employers will also owe them a duty to ensure that they are reasonably safe at work.[29] Given that some players play for both their club and Union (in international rugby), they may be owed such a duty by both entities in relation to the periods when they are working for each entity, respectively.

Such duties would likely be limited to ensuring that players were given appropriate medical treatment when injured (including appropriate advice on return to play) and that the applicable medical regulations were complied with. See, for example, the Cillian Willis case (discussed here) or the Matt Hankin case (discussed here).

3.3 Leagues?

A final question worth considering is whether a private league, such as Premiership Rugby, could owe players a duty of care. This author believes that they would.

All Premiership players are bound by the Premiership Rugby Regulations under their employment contracts. These regulations set out, inter alia, obligations in relation to medical matters, including head injuries.[30] For the purposes of the reported litigation, the regulations applicable at the time the claimant players played would be crucial, but the more recent regulations are indicative of a proximate relationship between the parties as regards safety.

Premiership Rugby’s regulations are drafted in agreement with the RFU, but Premiership Rugby takes on responsibility for the organisation of Premiership matches. It is a quasi-governing body and thus, this author would submit, falls under a similar duty of care towards players.

As above, the content of this duty would be narrower than that of World Rugby and the Unions but would share many of the same characteristics.

4. Conclusion

For the reasons explained above, World Rugby and the Unions are likely to owe duties of care to the players. This is a position supported by authority, and by application of the relevant tests. It is reasonably foreseeable that players would suffer (brain) damage if the governing bodies do not take reasonable care; there is a proximate relationship by virtue of the application of mandatory rules; and the controlling position of the governing bodies makes it fair, just, and reasonable to impose such a duty.

Though they have not yet been sued by the players, their former clubs will also owe the players a duty of care – and the league(s) may do so, too.

The more controversial question is likely to be the precise scope of these duties, and the way that they interact. The rugby landscape is such that various parties take responsibility for the safety of players at different times – and sometimes simultaneously. The reasonable expectations on each party will be discussed further in Part II.

Article by Ben Cisneros. Ben is a Trainee Solicitor at Morgan Sports Law, though this article reflects only the author’s personal views. Please email ben.cisneros@morgansl.com for any legal or media enquiries.

[1] Darnley v Croydon NHS Trust [2018] UKSC 50, [15]

[2] [2018] UKSC 50

[3] Ibid. [15]

[4] Ibid.

[5] Caparo v Dickman [1990] UKHL 2

[6] Darnley, [15]

[8] Ibid. [82]

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid. [85]

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid. [87]

[13] Ibid. [91]

[14] World Rugby Regulation 2.1.1 provides that:

“A Union…must ensure that it complies with these Regulations and must further ensure that it takes appropriate action to inform each and every one of its members of the terms of the Regulations and the obligation to comply with the same.”

[15] See, for example, Laws 24 and 27 of the Laws of the Game and World Rugby Regulation 10.

[17] Ibid. [21]

[18] Ibid. [19]

[19] Ibid. [17]

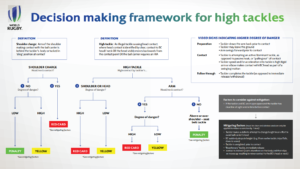

[20] See the Decision-making framework for high tackles.

[21] See, for example, World Rugby Regulation 10 and Law 27 of the Laws of the Game, which set out the Head Injury Assessment procedure.

[22] [2000] HCA 41, [10]

[24] Beloff M. et al, Sports Law (Hart, 2012), p.151.

[25] [2004] EWHC 140 (QB), [138]

[26] For example, the Laws of the Game, including rules relating to substitutions and dangerous tackles.

[27] See, for example, World Rugby Regulation 19.

[28] See RFU Regulation 9

[29] Wilsons and Clyde Coal Co v English [1937] 3 All ER 628